I’ve got something else for you to worry about, if you’d like to take your mind off cyanide in the subways, North Korean missile tests, and bucket drownings.

In the Atlantic Ocean, about 280 miles from the Moroccan coast, is the lovely island of La Palma. It is part of the Canaries archipelago, and is known as La Isla Bonita for its sun-drenched natural beauty.

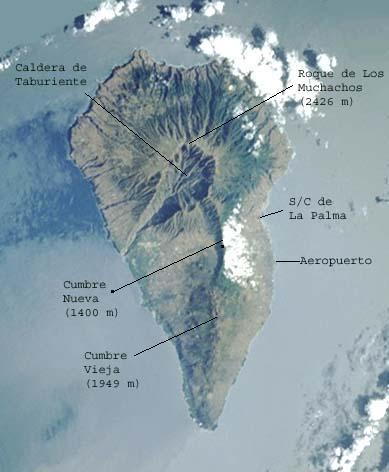

Though small, La Palma rises dramatically from the sea. The summits of its central range tower above the nearby coast, and the highest peak, Roque de los Muchachos, which supports an astronomical observatory, reaches almost 8000 feet above sea level, which means that it soars more than 21,000 feet above the surrounding abyssal plain. And as is so often the case with small but steep islands, La Palma is an active volcano.

The tapering southern half of the island is divided by a ridge called the Cumbre Vieja, and along this crest are no fewer than 120 volcanic vents. There has been a good deal of recent volcanic activity here, with eruptions in 1470, 1585, 1646, 1677, 1712, 1949, and 1971. In the 1949 eruption, the ridge fractured, and an enormous chunk of it slid some distance toward the sea.

Geological examination has revealed that this ridge, made of porous material as are most volcanoes, is divided internally by vertical dikes of impermeable rock. These walls form chambers that trap water, and it appears that during eruptions the water, heated by the upwelling magma, vaporizes in these pockets, exerting considerable lateral pressure. The worry is that the next eruption might send five hundred cubic kilometers of rock splashing all at once into the Atlantic, with undesirable consequences.

The worry, of course, is a tsunami. Although they can contain enormous amounts of energy, tsunamis caused by undersea earthquakes, such as the disastrous Christmas wave of 2004, are usually no more than 30 or 40 feet high when they strike the shoreline. Still, they can cause tremendous damage, because of the colossal amount of water lifted: rather than simply passing by after a few feet, such a wave can be a mountain of water thousands of feet from front to back. But when waves are caused by titanic rockslides, they can be much, much taller. There was an event in Lituya Bay, Alaska, on July 10th, 1958, in which an earthquake and landslide in Crillon Inlet generated a wave that stood almost 1000 feet high, and which scoured the opposite headland to a height of 1500 feet.

Such events are called megatsunamis, and are exceedingly rare, but there is ample geological evidence that they have happened again and again in Earth’s long history. And an investigation by geologists Steven Ward and Simon Day suggests that if the Cumbre Vieja ridgeline fails during an eruption, it could trigger a megatsunami that would race across the ocean at jetliner speeds (as tsunamis do) and fall upon the Eastern Seaboard of the United States, nine hours later, as a wall of water over a hundred feet high.

There are those who say such a scenario is inevitable, but there are also those who say it is very unlikely, on the theory that the landslide would be gradual. Readers are encouraged, as always, to make up their own minds, and plan accordingly.

2 Comments

Since “Yikes!” is getting kind of worn out, I’m going to pass on this one, and worry about N. Korean nukes instead.

– M

OK. I’ve got worrying about this one covered.