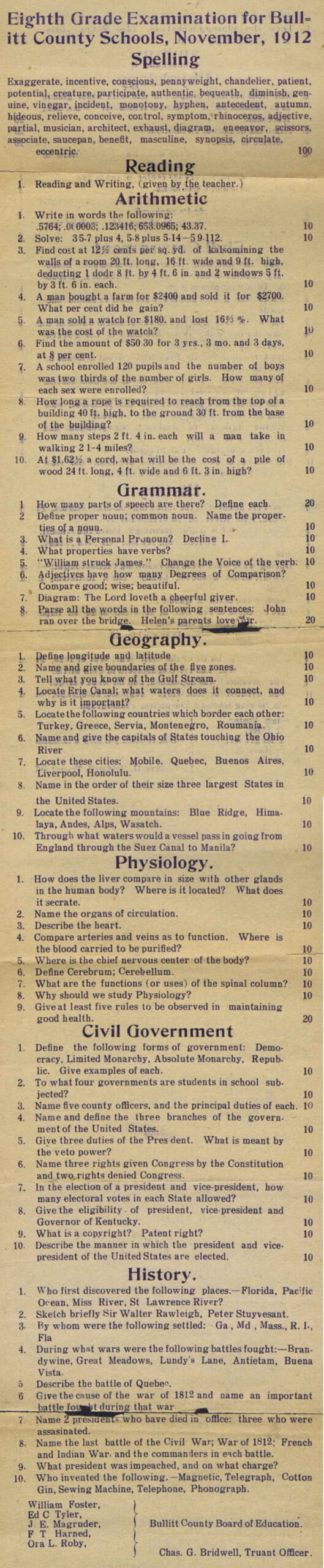

Making the rounds yesterday was an image of an examination paper for the eighth-grade students of Bullitt County, Kentucky, back in 1912. I very much doubt that most college-educated adults could pass it today.

One might argue that there is no longer any need for a person to carry around this much general knowledge, as it’s all at our fingertips, right there on the Internet (to which we are connected in every waking moment). But the thing about knowledge is that the more you actually have, the more you realize you don’t have; you might say that epistemic hunger acts inversely to the physical kind, and the more undernourished you are, the less you realize it. (I once heard a Southern friend describe an ignoramus of his acquaintance by saying “He don’t know nothin’. Why, he don’t even suspect nothin”. That sums it up perfectly, I think.) The information on the Internet does you no good at all if it never even occurs to you to look for it.

An advantage of actually knowing things is that you never know which of the things you know is going to provide the key to making sense of something seemingly unrelated. The broader the scope of your knowledge, the more you can see patterns, connections, metaphors, and similarities between new and unfamiliar things and stuff you’ve learned before, and still have knocking around in your head. If you keep up the habit of learning as an adult, that store of information can gradually build toward a kind of critical mass that makes it easier and easier to solve problems, figure things out, and make more accurate predictions and better decisions. Yes, just about any information is somewhere out there on the Internet, but it won’t do you any good if it never occurs to you to look for it.

Here’s the kicker: the importance of the things I’ve just pointed out above about the value of “book larnin” was itself, once upon a time, something that every civilized adult knew, and that’s why, a century ago, even eighth-graders were expected to know things, and, more importantly, were trained, willy-nilly, in how to learn. (How so? By being exposed to knowledge, and forced to learn it. Nothing teaches you how to do something as well as simply being made to do it, and learning how to learn is no exception.)

I have reproduced the examination below. Take a crack at it, and see how you do.