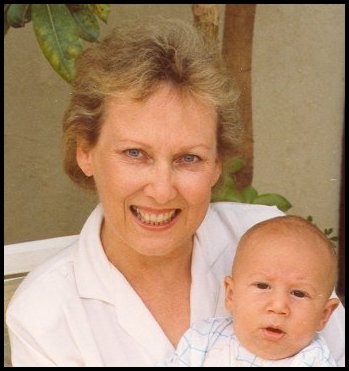

My mother, Alison, died in Oceanside, California on March 28th after, as they say, a brief illness. She was seventy years old.

Alison was born in Glasgow, Scotland, in 1935. Her father, Ralph Calder, was a Congregational minister, and her mother, Elsie Morrison, was the daughter of Alexander Morrison, a well-to-do tanner from Tullibody, a small town in Clackmannanshire.

Shortly before she died, I sat with my mom and asked her to reminisce a bit about her early life.

She recalled the bombings in Glasgow – the Nazis had their eye on the shipyards of the Clyde, and once the silent early months of the war had passed, and the conflict began in earnest, there began to be frequent raids. She remembered losing a beloved teacher, as well as a friend’s father, to German bombs, and her own family’s roof being blown off.

In 1941 her family, which now included her younger sister Shiena, moved to Edinburgh, which was a much quieter place, because, as she explained to us, while Glasgow had all the shipyards, Edinburgh only had a marmalade factory. Once there, at the tender age of six, she began to attend a school called Edinburgh Ladies’ College (which has since changed its name to Mary Erskine’s School). The institution’s claim to fame, my mother recalled, was that Felix Mendelssohn’s daughter had been a student there, and the composer had written a processional march for the school. It was in a lovely part of the city, and my mother was very happy there.

After the war, though, her father took a position in London, so the family moved once again. My mother was twelve at the time – not a great age for being uprooted from one’s friends – and she didn’t like London at all. Edinburgh is a lovely city, with an ancient castle rising above the center of town, and London seemed grimy and ugly by contrast. (“Where’s the middle?” she said she remembered thinking.) To make matters worse, she was soon sent off to boarding school – a place called Milton Mount, in Crawley, West Sussex – and had a hard time fitting in, having arrived in the middle of the year with her Scottish accent and unfamiliar ways.

My mother was never meek, nor was she the sort who would patiently suffer scorn and unsympathetic discipline, so she gathered her things and ran away, making her way back to London, where she pled her case to her parents. Her father, however, although an admirable man, was not particularly soft-hearted, and said he would think more of her if she went back. So back to Milton Mount she went.

She was never happy at the school, though, and when she was sixteen – at which time students choose whether to test for further education – her willful and contrary side got the better of her, and she took her School Certificate (the equivalent, roughly, of a high-school diploma) and left. She would look back on this as an unwise decision, but at the time she was just fed up.

[As it happened, I did pretty much the same thing – I chafed a great deal in educational institutions in my teens, and when my high school, after skipping me ahead a grade with a promise that I could graduate early, told me they had made a mistake, and that I would have to come back after my senior year to make up an assortment of ninth-grade credits, I just dropped out, and took the GED test a little later. Everybody thought my attitude was crazy, and that I was “cutting off my nose to spite my face”, but I didn’t care. Now I know where I got it from.]

After leaving Milton Mount, Alison spent a year in something she described as a “journalism school”, then tried her hand at a few jobs, but feeling unsatisfied, and with a yen to do something, as she put it, “useful”, she decided to go for nurse’s training at St. George’s Hospital in London. This would have been in 1953 or so.

There she met my father, who was an intern (nine years older than Alison, he had been a medic in the Royal Navy during the war), and they fell in love. On December 4th, 1954, they were married. My mother was 19.

They were restless, and considered going to India to work in something resembling the Peace Corps. But they could not find a situation where they could be assigned as a couple, and when my father was offered a job in Vancouver, they set off westward. They sailed to Halifax, then traveled by train across the wintry vastness of Canada to begin their new life together.

I don’t think they liked it much in Vancouver, though (they were living in in area called New Westminster), and after a couple of years (during which I arrived on the scene) my father received another offer, this time to come to New Jersey to work in the research labs of Ortho Pharmaceuticals, a division of Johnson and Johnson. In October of 1956, when I was five months old, we emigrated to the USA, and settled in a pleasant apartment at 12 Dickinson Street in Princeton, just a few yards from the University.

This was the beginning of a quiet and prosperous time for my family. My younger brother David was born in 1961, and my father’s work went very well: during his time at Ortho he developed the immune-globulin serum that led to the eradication of Rh disease, for which he received the Lasker Award, among other honors. As a result he rose to be Director of Research at Ortho, and times were good for the Pollacks.

In about 1965, though, my mother, then just 30, began to notice some stiffness in her hands, and before long she was in a fair deal of pain. She was soon diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis, the disease that would progressively ravage her body as the years went by, and that would later kill her. This was a heavy blow; she was an active and athletic woman, who enjoyed tennis and Judo, and who also had two young children to look after.

The arthritis worsened rapidly, and she soon found that the only available relief was in cortisone, which she began to take regularly. Cortisone damages the endocrine system, and her health slowly began to deteriorate.

Nevertheless, she was never one to feel sorry for herself, and, looking for new challenges, she turned her keen mind to the pursuit of a degree in physical anthropology at Rutgers University. She went so far as to acquire a Ph.D., in the course of which she conducted a still-quoted study of sex differences in stress physiology, using the New Jersey State Police as her test group. (I still remember the refrigerator full of cop urine we had in the basement.) After receiving her doctorate she continued to teach at Rutgers for several years.

In the late 70’s my father left Ortho to work for Purdue-Frederick, and my parents moved to Weston, CT for a few years. In 1985, just as my daughter ChloÁ« was born, they moved once again – this time to La Costa, California, to start a small pharmaceutical company of their own. My mother liked it there – she had felt hemmed in in woodsy Connecticut, and the bare hills of Southern California reminded her of the beloved Scottish countryside.

By now my mother was already suffering a great deal with her disease – her hands had become warped and weakened, and it was becoming ever more difficult for her to walk on her disintegrating feet. And as the years went by in California, the years of steroid drugs began to take a heavy internal toll as well – muscles and ligaments began to fail throughout her body, and her immune system began to lose the battle. Finally, this past February, we learned that a recent weeks-long bout of nausea had been caused not by a stomach bug, but by a vicious and fast-growing tumor. A month later she was gone.

My mother was an extraordinary woman. She was enormously intelligent, with a wonderful command of language, and an amazing gift for conversation. She was kind and loving, and fiercely loyal to her friends. She was proud of her Scottish ancestry, but was utterly free of any cultural or racial prejudice, meeting everyone on equal terms, always with an open heart and an open mind. While she had no patience for the foolish and pretentious, she spoke quietly and politely – I cannot recall a single exception throughout her entire life – to everyone, always, no matter what the circumstances. Despite suffering for decades with a crippling and painful disease that stripped her, by the end, of the ability even to raise her arms to fix her hair, or to grasp a pencil, she never, ever, ever complained or sank into self-pity. She had a terrific sense of humor, and loved nothing more than a good laugh with friends. She was absolutely selfless in caring for others, and I practically had to tie her to her chair, whenever I came to visit, to keep her from getting up to clear the dishes, etc., even when she could barely walk. She was a constant, devoted, caring and true companion to my father for 51 years. And never, never, never, even during my tempestuous adolescence, when I would have made Vlad the Impaler seem like a welcome houseguest, did I ever doubt for one second that she loved me with all of her heart.

She was a wonderful, inspiring, beautiful, sweet, generous, thoughtful, and utterly unique woman, and I am prouder than words can express to be her son, and to have shared her time on Earth. My heart breaks to think that she is gone. Please, please, if there is a God in Heaven (and how I wish I knew) – please, be kind to her gentle and loving spirit.

Thanks so much, Mom. Goodbye. I love you.