I had a post ready to go here yesterday, but I sent it off to American Greatness and they picked it up, so I’ll ask you to read it there.

Note: a disclaimer about the reality of the pandemic didn’t make the final cut. I’ll I’ll post the unedited, and possibly slightly revised, version here tomorrow.

Update, 7/31: Here’s the article as submitted to AG:

* * * * * * *

Here we are, a little over halfway through 2020. Events have moved so quickly that most people can hardly keep up, and are simply coping as best they can. More has changed in these past few months than at any other moment in our lifetimes, and many things that would have seemed unimaginable just a year ago have come to pass. 2020 has ratcheted us into an entirely new world — and it is in the nature of ratchets that they don’t move in reverse. Let’s survey the damage.

China, rocked back on its heels by America’s having stood up at long last to its cheating and bullying, released a plague upon the world. (Whether the outbreak was planned or not, it is clear that the CCP intentionally suppressed warnings about it, and allowed it to spread around the globe. What better way to smash its enemies, America in particular, than to destroy their economies?)

The result over here was an immune response that nearly killed the patient. (It may yet.) A drastic quarantine was imposed upon the nation, and a roaring economy bludgeoned to its knees. Unemployment, which had been at the lowest levels in half a century (and for blacks and Hispanics, the lowest ever recorded) soared to Depression-era levels. Hundreds of thousands of small businesses failed.

Governors and mayors imposed this quarantine, severely restricting commerce and assembly, entirely at their whim. The determination of “essential” businesses and activities — which, for many smaller enterprises, meant the difference between life and death — was glaringly, often contemptuously, capricious.

Nietzsche famously defined happiness as “the feeling that power increases — that resistance is being overcome.” In politics, war, and international affairs, the temptation to see what you can get away with is always there, and times of crisis provide the ideal opportunity. (So well does this work that the cleverest and most ambitious will find a way to create a crisis if events fail to provide one.)

For many governors and legislators — in particular those Blue politicians and political strategists who, in this critical election year, felt themselves losing ground as the Trump-era economic boom continued — the “Wuhan Red Death” was a gift from heaven. Everyone knows that a good economy favors incumbents, and that hard times favor an expanded and maternal State — and so the sudden appearance of this pestilence was an astonishing stroke of luck, a kind of <em>deus ex machina</em>. Opportunities to seize emergency powers are as rare as Willie Wonka’s Golden Ticket; usually one has to start a war, or burn down a parliamentary headquarters, to create them. Yet here was just such an opportunity, tied up with a bow and stamped “Made In China”. Our overlords lost no time.

Think of what we’ve lost:

— Professional, amateur, college and high-school sports, as well as youth athletic leagues: gone. (Yes, there is some baseball now, but in empty stadiums — and the prospects for football, basketball, etc. are dim.)

— The schools are all closed. This means in turn that parents who depend on the schools to look after their children during working hours cannot return to the workforce.

— The entire movie industry: gone.

— Theater: gone.

— Concerts: gone.

— Summer camps: gone.

— Bars: gone. (Here in Massachusetts, they will be closed until there is a vaccine, which for many, if not most, is a death sentence.)

— Restaurants: either closed, or operating under draconian restrictions. Many places still do not allow indoor dining, and those that do permit it only at reduced capacity. The restaurant business has thin margins under the best of circumstances, and you can be quite sure that nearly all restaurants are currently losing money.

— Travel: decimated. (This includes hotels, car rentals, etc.)

— Public gatherings: churches, parties, funerals, weddings, reunions, school commencements, club meetings, cookouts, marathons, and so on: gone.

That’s only a partial reckoning — but what a list it is! If one were asked, a year ago, to name the things that make up ordinary civic life in America, it would have been, more or less, the same list. All gone. (A year ago, could we have imagined a New York or Boston without an open bar? But here we are.) Meanwhile our governors, giddy with power, decide for us daily what we can or cannot do — our basic right “peaceably to assemble” notwithstanding. Jog by yourself on a beach? Attend an outdoor funeral? You’ll be arrested. Form a mob of thousands and crowd the streets to bray about an officially sanctioned political grievance? By all means, please proceed.

Flourishing societies strike a healthy balance between rights and privileges. When either grows too much at the expense of the other, a nation declines: on the one hand toward impotent mediocrity, on the other into tyranny.

The rights in question here are not “negative” rights, of the sort found in the Constitution, which boil down to particular variants of a more general right not to be interfered with by the government, but rather positive rights — rights to goods that require expense and effort to provide — which necessarily involve a positive compulsion on someone’s part to provide them, effectively indenturing one segment of society to another. As more and more of these goods become mere entitlements, rather than rewards to be earned by productive labor, the burden upon the productive segment of society increases, even as that segment dwindles — and the nation sags toward impotent mediocrity.

Privileges, on the other hand, are by definition blessings bestowed by those in power. It is always and everywhere a hallmark of tyranny that all rights, even negative rights, become privileges, granted or withheld according to the interests of the powerful. That’s exactly what’s happening here: our supposedly inalienable rights to assemble, to do business, to worship in church, etc., have abruptly, and with no discernable process of public consent, become privileges. That is no longer the rule of law; it is the rule of men.

But this is not the only erosion of the rule of law we have seen in 2020. While millions of working Americans have, by decree, been forced to abandon their jobs and businesses, the streets of major cities have been taken over, with the compliant approval of mayors and governors, by angry anarchist mobs. These mobs have destroyed and defaced both public and private property, have terrorized citizens and repeatedly assaulted the police, and have committed crimes ranging from vandalism to looting to arson to murder. The police have tried bravely to maintain order, but have so far been overwhelmed — and in many cases even told to stand down as the rioters went about their business. Meanwhile the police have been consistently vilified and slandered as racist brutes, and in many of the cities where the rioting has been the most dangerous, politicians have pledged to reduce funding for their police departments, or eliminate them altogether.

So: with supposedly rights-bearing citizens commanded by fiat to stay home and shutter their businesses, violent mobs running wild in the cities, and the police under withering assault not only from the mobs they face, but also from a hostile press and their own mayors and city councils, we can add “rule of law” to the list of things we have lost in 2020.

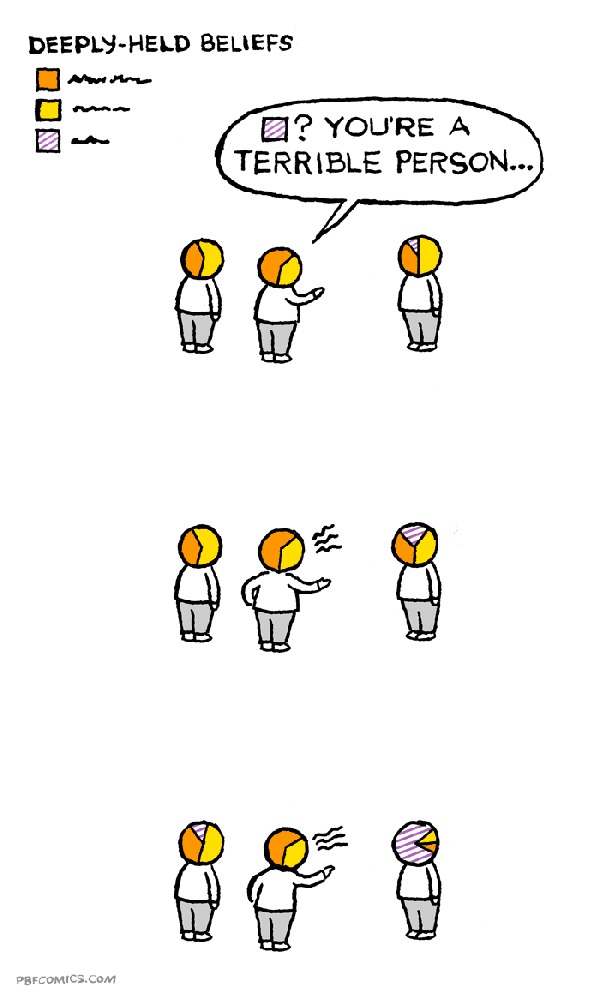

Here’s another thing we’ve surrendered: our faces. The face we present to the world is our “sigil”, our flag of individual distinctness. More than simply that, though, our faces, and the richness of expression they make possible, are a primary medium of interpersonal communication. They are the book in which others naturally and instinctively read our characters, our thoughts, and our moods. To “show one’s face” is the most basic act of participation in civil society; to “lose face” is always and everywhere painful and humiliating. When we “face” one another we connect and interlock as social beings; there is a reason why popular “social”-media platforms have names like Facebook and Facetime. Why do fundamentalist Muslims insist upon covering the faces of their women? It is precisely to prevent this connection, this humanizing and socializing interaction. It is a means of possession, of control.

Now, like the burqa-clad women of the Dar al-Islam, we all must cover our faces, except in the isolation of our homes. The effect of this is powerfully levelling and atomizing; it works in an insidious way to break down the horizontal ligatures that bind us together as a society. And as we sit unemployed at home, awaiting our relief checks, the result is an increasing deflection of all social connections from the horizontal to the vertical: away from the people around us, and toward the sovereign power above us — from which all blessings increasingly must flow. In this way, with every faceless and “socially distant” passerby now a potential carrier of pestilence, attraction gives way to repulsion. We see fewer and fewer people in person, and keep more and more to ourselves, until that all begins to feel “normal” — and so we begin to lose another essential feature of American life: the richly rewarding human experience of being a distinctive and self-reliant member of an organic and multidimensional civil society.

Finally, we have already, to an alarming extent, broken up the foundation of what it has always meant to belong to the American nation: the shared belief that America is, in its roots and in its heart, something worthy and good. The bedrock of the American mythos — the Founding Fathers, the Constitution, the ennobling natural-law principles enshrined in the Declaration of Independence, the confidence in the approval of Providence expressed in our national motto, and the sense that we are links in a great chain that connects the sacrifices of our ancestors with the duty of living Americans to preserve the blessings of law and liberty for our children’s children — these have all fallen away, precipitously, in this annus horribilis. What once we cherished, we now are taught to despise. But how long can a nation that disgusts itself continue to exist?

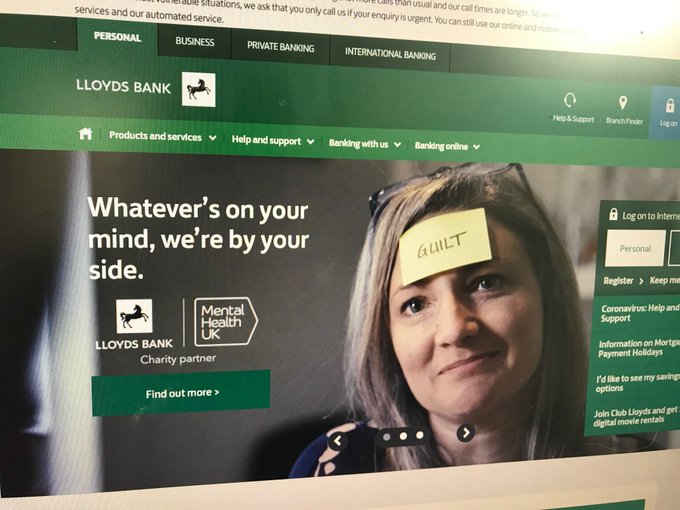

(None of this is meant to suggest that the pandemic wasn’t real, or that the risk didn’t justify prudent precautions. But in our time, after generations of unprecedented peace and security, we seem to have have succumbed to an enfeebling condition that the psychologist Jonathan Haidt calls “safetyism” — a degeneration of the spirit in which the fear of harm or loss overwhelmingly outweighs all other principles and practical concerns. In the era of COVID, the public-policy formula seems to have had a combination of safetyism, political strategy, and the heady temptations of power on one side of the equation, and almost nothing at all on the other.)

All of this, and more, have we lost in the space of less than a year — yet most of us have simply … adjusted. For those of us old enough to have the perspective of historical parallax, it is a disturbing reminder of some of humanity’s darkest lessons: lessons that far too many of us seem to have forgotten, if we ever learned them at all.